The Cooking of Coal: A Bennett's Valley Legacy

Excerpts from the book The Beehive Coke Years by John K. Gates

Simply explained; “The coking process consists of heating coal in the absence of air to drive off the volatile compounds; the resulting coke is a hard, but porous carbon material that is used for reducing the iron in the blast furnace”

I, however, relate better to the explanation used in the movie “October Sky” When confronted by his teenage son about why his father desired to be a coal miner, he replied “You listen here!, The coal we mine makes steel, and if steel fails this country fails. If you had half a brain in your head you’d know that!”

Coking was hot, hellish, backbreaking work. At the time, the choice was work in the mines, or the coke ovens.

The local mines and coke ovens employed many European immigrants, who left their homeland to come to America, and a better way of life. Still today, many area residents can trace their ancestry to these resourceful people.

These people came to America with a promise to apply their great work ethic. While the men were working the coal, the women, among their many chores, did their daily battle with the coal dust that found its way into every opening in the house. Families lived meager lives in the early days, but they were close knit.

Early in the century, immigration reached its peak. Some companies held classes in Americanization. The miners were taught English, American History, writing etc., to make it easier to obtain citizenship papers.

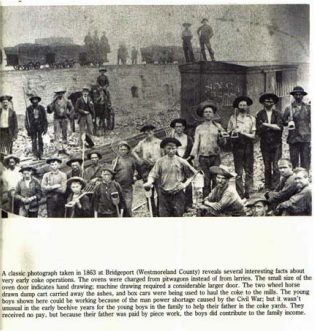

The first step in coking was charging the oven with the mined coal. This was achieved by the Larry Car. The Larry Car ran on the track on top of the ovens. The following 4 photos show how the Larry Car evolved from being manpowered or horse/mule powered. Later a small steam engine was used, then finally the electric Larry.

The electric Larry Car operated on 250 Volts D.C. generated on site. A man stood on the rear of it, and its speed was controlled easily through a large bank of resistors with a hand lever control. It had a mechanical brake. The operator was called the charger.

It took a 1 1/2 ton charge of coal to yield 1 ton of coke. A typical charge of coal was between 4 and 5 ½ tons. After the charge was complete, the charge had to be leveled. The leveler did this with a large toothless rake attached to a very long handle.

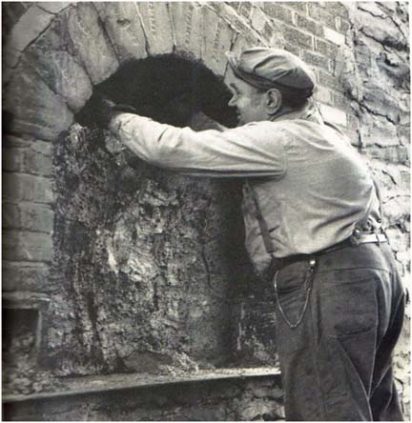

The next step was to seal the front opening. This was done by the mason, who used the same bricks many times over. The mortar mix contained some of the coke dust or “breeze”.

The opening was typically mudded to within 2″ of the top. The typical burn time was 48 to 72 hours and reached temperatures of 2000 Degrees F. The burn time was regulated by the size of the charge and the size of the opening. A burn of 96 hours was sometimes done on the weekend as the ovens were not manned on Sunday. The inside dimensions of the ovens in this area was 12 ½ feet on the bottom and 5 ½ feet high. There are 3 sites in Bennett’s Valley; the largest by far is at Tyler with 380 ovens. There were smaller operations at Byrnedale and Glen Fisher.

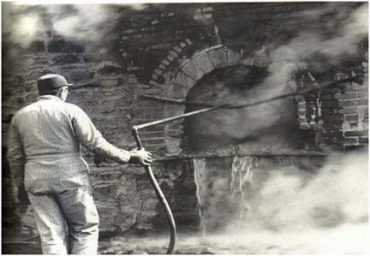

After the coal was transformed to coke, the next step was to pull down the brick and mortar and begin quenching the coke. This was an important job, requiring skills built through experience. The coke could not be drenched or it would not “start up” properly in the steel furnace. It also meant starting at 3:30am. This was done to have ample time to cool before drawing the coke.

These are some of the tools of the trade. The tool on the left was the leveler, used to level the coal in the oven. The large pitchfork was used to load finished coke into wooden wheelbarrows, and then the railcar.

The finished coke was loaded into rail cars by hand and shipped to steel foundries. The finished coke left our area via the Buffalo and Susquehanna RR. This now abandoned grade was a key link to the mills which consumed the coke made here in Bennett’s Valley. In its heyday, the mines and coking industry were an integral part of the American steel industry.

The coke works at Tyler have several ovens that are intact. These ovens were owned originally by Cascade Coal and Coke. The site is on state owned land and across the road from where the Hollywood AMD treatment facility will be built. The area mines and coke works are the reason for the AMD project. The site, located just 200 yards off Tyler Road, could be made accessible to all and would be a great self guided historic site. The stone fronts that are seen in the photos, were used in CCC projects years ago. Although, there are some in the rail pit in the center of the site. With the proper signage and documentation, the site could be brought to life and be a destination for school field trips, etc. Several states have coking historical sites, complete with bluegrass festivals and summer celebrations. This abandoned coke works, with its proximity to Parker Dam State Park and the ongoing tourism effort for the PA Wilds, would be a natural fit. Contact the author of this article at jas427@windstream.net to make a comment or ask questions.